Ohio State students returning from their Thanksgiving break last November had their first day back on campus shattered by one of their fellow students, Abdul Razak Ali Artan. He drove his brother's grey Honda Civic into a crowd gathered outside Watts Hall on campus, injuring a number of them. He then emerged from the wrecked vehicle with an eight-inch knife and began attacking bystanders, some of whom were already tending to the injured.

The Islamic State would hail Artan the very next day, calling him a "soldier" and praising him for responding to their call for Muslims living in the West to conduct terror attacks in its name.

Artan, however, isn't the only Islamic State "soldier" from Ohio to answer the terror group's call.

In fact, a growing number of ISIS supporters and operatives have emerged from the Buckeye State over the past two years. The ISIS-inspired terror attack at Ohio State on November 28, 2016, should have been a wake-up call to the escalating problem in the state, but that doesn't appear to be the case. Rather, the terror incident is yet another example of how the problem has been buried while the threat has metastasized.

Buckeye Battle Cry: "Run, Hide, Fight"

The pageantry of a football game at Ohio Stadium is among the top spectacles in American college athletics, with 100,000-plus fans (usually) cheering their team on to victory. The bells ringing after a score. The "Skull Session" with the football team and the marching band prior to the game. And the band's entry into the stadium at the beginning of the game, leading the crowd with Ohio State's fight song, "Buckeye Battle Cry."

But after Abdul Razak Artan's terror attack last year, Ohio State has a new fight song, as do hundreds of other college campuses: "Run, Hide, Fight."

Artan's victims didn't have much time to run and hide when his car jumped the curb and rammed into a crowd of students. Eleven people were injured, most by the car-ramming; two were slashed by Artan with his knife. One victim had a fractured skull. Artan was shot and killed by a campus police officer two minutes after the attack began.

It was the first semester for the Logistics Management third-year student at Ohio State's Fisher College of Business, having graduated cum laude in May 2016 with an associate's degree from Columbus State Community College.

On his first day on campus, Artan was interviewed by the Ohio State student newspaper, The Lantern. He whined to the reporter about the absence of places for Muslims to pray on campus (there is a dedicated room at the student union) and about misconceptions other students might have about him and Islam if he prayed in public. The reporter later related how quickly Artan was able to recite from memory the laundry list of Islamic grievances, and his perception that Muslims were under siege in America from pervasive Islamophobia.

Among the courses he was taking that first semester was a class on "microaggressions" called "Crossing Identity Borders," where students are encouraged to "identify ways in which they can challenge or address systems of power and privilege."

One might say that given Artan's background, he had already been the beneficiary of privilege.

Born and raised in Somalia, he and his family lived as refugees in Pakistan from 2007 until 2014, at which time they moved to the U.S. and received legal permanent resident status. Among the stated reasons for his family moving to America was his mother's concern that she didn't want Abdul Razak and his siblings being recruited by the Somali terror group Al-Shabaab.

First landing in Dallas for a few weeks, they were resettled in Columbus -- home of the second largest Somali community in the country. He apparently quickly enrolled at Columbus State, which has one of the largest Muslim student populations of any higher education institution in America.

Artan's friends in Ohio and Pakistan claimed that he "loved America," but that contrasts dramatically with the Facebook post he left just three minutes before his attack:

In that post, he lashed out at how he was "sick and tired of seeing my fellow Muslim brothers and sisters being killed and tortured EVERYWHERE." He specifically identified "Muslims being tortured, raped and killed in Burma," which led him to "a boiling point."

He later wrote: "Stop the killing of the Muslims in Burma." Paradoxically, he also complained: "America! Stop interfering with other countries, especially in the Muslim Ummah."

"If you want us Muslims to stop carrying out lone wolf attacks, then make peace with 'dawla in al sham'" -- meaning the Islamic State. He later praised "our hero imam Anwar Al-Awlaki," giving a nod to the popular American al-Qaeda leader who was killed in a CIA drone strike in Yemen.

The pre-attack Facebook post concluded by saying:

By Allah, I am willing to kill a billion infidels in retribution for a single DISABLED Muslim.

The following day, the ISIS Amaq News Agency claimed credit for the attack, calling Artan a "soldier" of the Islamic State.

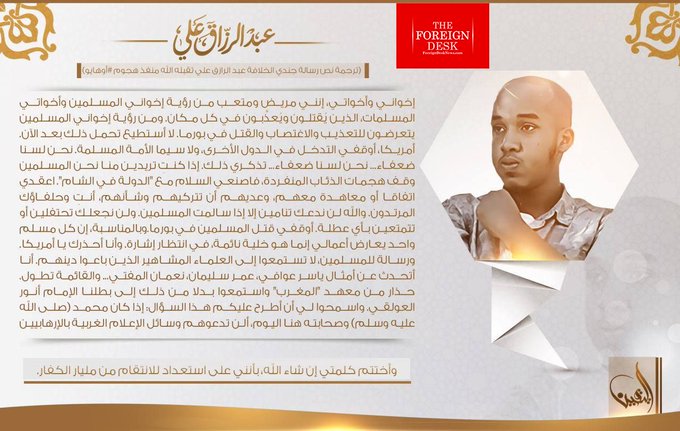

Later that week, Artan was featured in an article in the ISIS Al-Naba magazine praising him for responding to the call for Muslims in the West to conduct attacks, and calling for a "continuation of attacks in America":

ISIS media outlets later translated and published Artan's Facebook post, circulating it on various social media platforms:

So far, there's been no evidence made public indicating he communicated directly with anyone from the terror group.

The response to the Ohio State ISIS-inspired attack followed a well-established pattern: he was a "good kid," his family was clueless to his radical views, no one saw the attack coming, no one at the local mosque ever saw him, etc.

Columbus City Council President Zach Klein said the attack was an "isolated incident," despite the fact another Muslim immigrant, Mohamed Barry, had attacked customers with a machete at an Israeli-owned deli on the northeast side of Columbus just a few months before the Ohio State attack. Barry was shot and killed a half-hour following the attack when he lunged at police with the machete and a knife shouting "Allah akhbar."

Ohio State President Dr. Michael Drake was asked at a press conference whether the attack was terror-related. He replied that no one should jump to conclusions and that the incident had nothing to do with the Somali community in Ohio.

Being a university, a special species of lunacy was exhibited following the attack.

One Ohio State administrator posted a plea for sympathy for Artan on her Facebook page -- which she strangely asked people not to share -- emphasizing that he was "a Buckeye, a member of our family." She included a #BlackLivesMatter hashtag.

The week following the attack, a campus group, OSU Coalition for Black Liberation, gathered in front of the main library on campus and eulogized Artan along with other "people of color" killed by police.

As one of the group's leaders explained:

“We broadened the scope of what today was supposed to be, to talk about the aftermath of what happened on the 28th -- to talk about what it meant for that attack to happen and also for Ohio State to be a focal point for a lot of right-wing pundits, Islamophobia and xenophobia,” said Maryam Abidi, a fourth-year in women’s, gender and sexuality studies.

Officials at the Abubakar Assidiq mosque, where Artan reportedly attended less than a half-mile from his home, played dumb. Despite neighbors telling the media that Artan was devout and prayed at the mosque daily, Horsed Noah, director of the mosque, told reporters he didn't recall seeing Artan.

Mohamed Dini, the mosque's board chairman, lamented to Voice of America that no other incident had been associated with the community before. In fact, top Al-Shabaab commander Dahir Gurey had previously attended the mosquebefore joining the terror group, and other Somali leaders said that the mosque was known for terror fundraising and recruitment. That notwithstanding, the mosque leadership vowed to combat online extremism and radicalization following the Ohio State attack.

Artan's funeral was held at another predominately Somali mosque, Masjid Ibn Taymiyya. The mosque's founder, Nuradin Abdi, had been convicted in an Al-Qaeda plot to shoot up a Columbus shopping mall on Black Friday after Thanksgiving, and was later deported after serving his prison sentence.

Predictably, both the Ohio newspapers and the national media ran with the "Muslims fear backlash" angle, none of which actually followed.

In just a few days, all the news trucks, cameras, and national media personalities left town with many questions unanswered about this ISIS-inspired attack at the largest college campus in the U.S. The story disappeared just as quickly from local media as well.

Very little else has been reported since, save Artan's family saying they were mystified by the attack and a few snippets of information from when the mediaobtained the 534-page police case file:

Among the few discoveries was a note that Artan had left behind encouraging his family to reject being "moderate Muslims" and again pledging his allegiance to the Islamic State.

The Associated Press reported:

A man responsible for a car-and-knife attack at Ohio State University last year left behind a torn-up note in which he urged his family to stop being “moderate” Muslims and said he was upset by fellow Muslims being oppressed in Myanmar, The Associated Press has learned.Abdul Razak Ali Artan also told his parents in the note, reassembled by investigators, that he “will intercede for you in the day of Judgment,” according to the investigative case file of the attack obtained through an open records request.“My family stop being moderate muslims,” says the handwritten note transcribed by investigators and found by Artan’s bed in his family’s apartment.Artan also wrote: “In the end, I would like to say that I pledge my allegiance to ‘dawla,’” an Arabic word that means state or country and a likely reference to the Islamic State group. “May Allah bless them.”He concludes by saying he’s leaving his property to his beloved “but yet ‘moderate mother.’”Artan’s family was baffled by that note, which caused them a great deal of anguish, said Bob Fitrakis, a Columbus attorney representing the family. To this day, the family has no idea why Artan took those actions, he said Thursday.“The family is mystified by what happened. They’re absolutely clueless,” Fitrakis said.

And basically that has been it in terms of explanation for this ISIS-inspired attack in the heart of America.

But in the next segment in this "Buckeye Jihad" series, I'll look at another case of Ohio State students who weren't content to wage their jihad in Ohio. They left their adopted home to travel to the Islamic State in Syria.

But how did they get there -- and did they receive help?

Stay tuned for Part 2.

No comments:

Post a Comment