California Has a Housing Crisis and Can’t Figure Out How to Solve It

Here’s just one tidbit from California’s housing affordability crisis: According to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, families in the northern California counties of San Francisco, San Mateo, and Marin who make as much as $117,000 a year are eligible to live in low-income housing projects. Want another one or two? Well, here you go: California’s median home value has increased by almost 80 percent to $544,900 since 2011, while more than half of renters spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing.

Here’s just one tidbit from California’s housing affordability crisis: According to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, families in the northern California counties of San Francisco, San Mateo, and Marin who make as much as $117,000 a year are eligible to live in low-income housing projects. Want another one or two? Well, here you go: California’s median home value has increased by almost 80 percent to $544,900 since 2011, while more than half of renters spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing.

Not that there’s much of a mystery of what’s really happening. As the Los Angeles Times notes, “Academic researchers, state analysts and California’s gubernatorial candidates agree that the fundamental issue underlying the state’s housing crisis is that there are not enough homes for everyone who wants to live here.”

A few examples: UCLA researchers find, “Opposition to new housing and increased housing density are major components of California’s current housing problem. In many of the state’s cities a vast majority of residential land is zoned only for single-family housing, which drastically limits potential supply.” Likewise, experts at UC Berkeley conclude that “it is clear that supply matters, and there is an urgent need to expand supply in equitable and environmentally sustainable ways.”

I mean, this is just basic supply-and-demand economics. As Edward Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko wrote in the Winter 2018 edition of the Journal of Economic Perspectives: “When housing supply is highly regulated in a certain metropolitan area, housing prices are higher and population growth is smaller relative to the level of demand. . . . The great challenge facing attempts to loosen local housing restrictions is that existing homeowners do not want more affordable homes: they want the value of their asset to cost more, not less.”

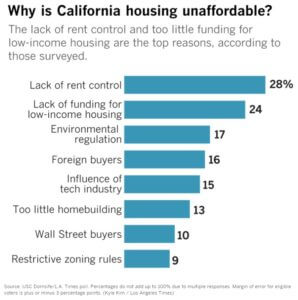

And as the above chart suggests, Californians are either ignorant of the economic forces at play here, or they choose to engage in an act of self delusion. An initiative on the ballot next month, Proposition 10, would repeal prohibitions on rent control in many cities and counties. This is exactly what the state doesn’t need. As a Brookings analysis finds: “While rent control appears to help current tenants in the short run, in the long run it decreases affordability, fuels gentrification, and creates negative spillovers on the surrounding neighborhood.” And yet a recent survey finds voters are closely split on the measure, although it is expected to lose.

And why should non-Californians care? It’s a big state, and it generates a lot of economic growth and innovation. And with better housing policy, it could be generating even more. As Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti wrote in a 2017 New York Times op-ed, “How Local Housing Regulations Smother the US Economy“:

https://ricochet.com/565600/california-has-a-housing-crisis-and-cant-figure-out-how-to-solve-it/Land-use restrictions are a significant drag on economic growth in the United States. The creeping web of these regulations has smothered wage and gross domestic product growth in American cities by a stunning 50 percent over the past 50 years. Without these regulations, our research shows, the United States economy today would be 9 percent bigger — which would mean, for the average American worker, an additional $6,775 in annual income. For most of the 20th century, workers moved to areas where new industries and opportunities were emerging. . . .What allowed this relocation to places with good-paying jobs that lifted the standard of living for families? Affordable housing. Today, this locomotive of prosperity has broken down. Finance and high-tech companies in cities like New York, Boston, Seattle and San Francisco find it difficult to hire because of the high cost of housing. . . . More housing in a region like Silicon Valley or Boston would raise the income and standard of living of American workers across the nation. The cost for the country of too-stringent housing regulations in high-wage, high-productivity cities in forgone gross domestic product is $1.4 trillion. That is the equivalent of losing New York State’s gross domestic product.

No comments:

Post a Comment